As part of our series CLC: Past and Present, Anna Barker reflects on the nature of the CLC as a continuous narrative which students follow throughout their school careers.

Submitted by Anonymous on Wed, 12/01/2022 - 13:29

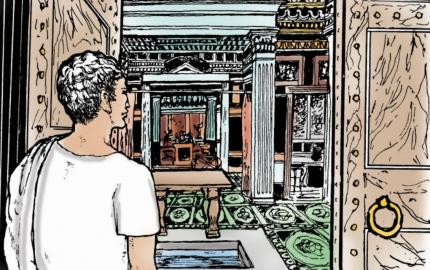

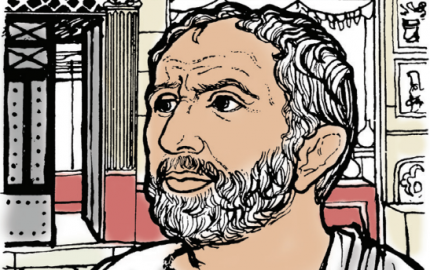

Grumio in the kitchen in Book I of the Cambridge Latin Course

What’s the longest time it’s taken you to read a book? Maybe a few months for A Suitable Boy. Perhaps you had War and Peace on the go for a year, or even, God help us, Ulysses.

Yet something quite extraordinary takes place in Latin classes in schools everyday, something which is almost never remarked on. Students of the Cambridge Latin Course read a continuous narrative over the course of three, four or in some cases five years. The story of the gens Caecilii, the Caecilius family, with the character of Quintus as the ‘hero’ at the heart, is told over five books, which can each roughly occupy a year’s worth of teaching. This means that a student can meet Quintus for the first time aged 11 and quite plausibly still be following his adventures aged 16. In the adolescent world of constant flux, there is something reassuring, grounding even, about reading a story set in the world of the late 1st century AD, with a cast of familiar characters. Given that, as adults, we probably spend a matter of days or weeks on a novel, what an extraordinary feat it is on the part of the Cambridge Latin Course to engage teenagers – a demographic not known for their commitment or attention span – over a matter of years. This on its own is remarkable, but in addition the story is of course written in a language which is not the students’ own, and an ancient one at that.

Students of GCSE Latin often seem nostalgic for the first book of the Cambridge Latin Course. It makes them feel grown up to remember Grumio the cook, Cerberus the dog, and, of course, Caecilius himself – the archaeological remains of whose house in Pompeii is always reliably mobbed by a group of British school children, to the bemusement of visitors of almost any other nationality. Each book – red Book I, blue Book II, green Book III, mustard Book IV, and the imperial purple Book V – acts as a shorthand for a particular school year, a particular mood and set of experiences. So when teaching indirect statement to students using the purple book, I have recently taken to doing what I call ‘red book nostalgia’ sentences: Caecilius dicit Grumionem cenam optimam parare; Caecilius dicit cenam optimam a Grumione parari etc. – using familiar characters and simple concepts to illustrate a challenging grammatical topic. It seems that there is something comforting for students about revisiting the characters of their Year 7 days when doing something as grown up as GCSE.

When talking about the concept of time in Latin, we talk about expressions of ‘time how long’ – for a day, for three months, for the summer holidays etc., – and expressions of ‘time when’ – at 3 o’clock, on Monday, in the middle of the night. ‘Time how long’ uses the accusative case (e.g. tres menses), whereas ‘time when’ uses the ablative (e.g. media nocte), a rule I summarise to students by the silly but somehow memorable acronyms THLACC and TWABL. The Cambridge Latin Course masters ‘time when’, creating fond memories for students of when they read particular stories and spent time with particular characters. As for time how long: show me another story which is read over the course of five years, or quinque annos, as the CLC itself might say.

Cambridge School Classics Project