The artifex Clara will replace Celer in the new Cambridge Latin Course. In this post, Director Caroline Bristow describes the research that shaped Clara's representation in the new UK and International edition and the evidence for working women in the ancient world.

Submitted by Anonymous on Fri, 24/06/2022 - 17:05

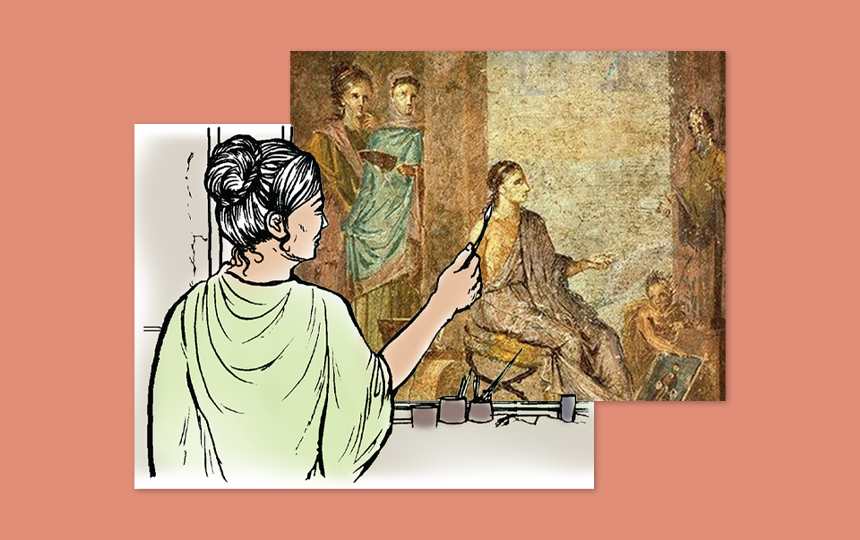

Clara paints a picture. The fresco is from the House of the Surgeon in Pompeii and depicts a female artist at work

Wealthy women like Metella may not have worked outside the home, but most women's lives involved far more than marrying and having children. Many households could simply not have survived without help from all their members, and so women in the ancient world often worked to support their families. Evidence for women in work is presented in this video from CSCP’s Romans in Focus materials.

The work that women pursued depended on family and social circumstances, such as whether a woman was freeborn. Women could contribute to family businesses, and some artisans trained female relatives in the skills necessary for their trade. For example, a young girl called Viccentia was learning to spin gold thread when she died and was commemorated by her parents (CIL 6, 9213). Freedwomen often pursued the line of work they learned when enslaved. Funerary inscriptions from Rome show that freedwomen might make a living as skilled artisans of cloth (CIL 6, 33920), silk (CIL 6, 9891) and gold jewellery (CIL 6, 9435). Ancient evidence indicates that women also worked as doctors (CIL 8, 24679), midwives (CIL 6, 9723), barbers (CIL 6, 37811), scribes and readers (CIL 6, 33473) to name only a few professions, while those without a trade often turned to selling food and goods in marketplaces. This work could be flexible and seasonal and would likely have suited women with children.

Although women’s contributions to family businesses are often unacknowledged in our sources, there were relatively few legal restrictions on women’s participation in the working world. Women were not meant to practice banking (Digest 2.13.12), Caecilius' line of work, but this did not stop them engaging in other kinds of commerce. In fact, Roman law acknowledged that women did manage and conduct business on behalf of themselves and others (Holleran, 2016). Some must have done so from necessity, like the widows who took control of their late husband's business affairs. Here are just a few examples of working women in Pompeii:

- Julia Felix owned a large, impressive house, in the atrium of which were a series of famous frescoes depicting life in the forum. It seems that she rented out property and owned a bar, restaurant and bath complex (CIL 4, 1136).

- Asellina owned a bar and supported some political candidates (CIL 4, 7873)

- Eumachia was a priestess of the cult of the emperor, patron of the cloth-workers (fullers) and an important benefactor. She financed the construction of one of the largest buildings in Pompeii (CIL 10, 810)

- Naevoleia Tyche was a women freed from enslavement who probably became wealthy through overseas trade using ships (CIL 10, 1030)

- The name Faustilla appears in receipts scribbled on Pompeii's walls, suggesting she was a moneylender and pawnbroker (CIL 4, 4528)

***

When the North American 5th edition of the Cambridge Latin Course was created, the decision was made to recast the painter, Celer, as a female artist, Clara, to prompt discussion of the many women who worked to earn their living. It is imagined that Clara is an artist who has lived and worked for many years in Pompeii. We first meet her in Stage 3 of the new CLC edition, when Caecilius employs her to spruce up his dining room by painting Hercules fighting a lion, one of his daughter Lucia’s favorite myths. Clara is encountered several times throughout Book I, including acting as our ‘guide’ around the Roman forum in Stage 4’s cultural background material.

As with all CLC stories and characters, great care was taken to base Clara on sound historical evidence. A wall painting from the House of the Surgeon in Pompeii shows a female artist at work, and a list of notable female artists appears in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History 35.40. Pliny praises their skill and notes that one of them was so much in demand that she was able to command the highest prices of any portrait painter.

The inspiration for Clara is Iaia of Cyzicus, one of the artists on Pliny’s list. Pliny tells us that she specialised in female portraits and was famous for a painting of an old woman from Naples. She was also known for a self-portrait painted with the help of a mirror. Clara is imagined to be an older woman working in the Bay of Naples and a master in her art.

The name ‘Iaia’ was, however, considered to be a little challenging for students beginning their Latin studies and so a replacement was sought. ‘Clara’ was borrowed from Verenis Clara, a freedwoman whose name appeared in a funerary inscription in the necropolis near Pompeii’s Nucerian Gate. Her name means ‘bright’ or ‘famous’ in Latin, which seemed to fit well with our Clara’s reputation as an accomplished artist.

The final hurdle to overcome in establishing this new character was one of the most important: getting the Latin right. In earlier editions of the CLC, Celer is described as a pictor, but the expected feminine form, pictrix, does not appear in any surviving classical Latin texts. As a plausible alternative, the decision was made to use artifex. Pliny the Elder used it to describe painters, and it was also employed pejoratively by Tacitus in Annals 12 to describe a woman who was an “artist” at poisoning people!

If elite literature is anything to go by, the idea of a freeborn woman working could sit uncomfortably alongside Roman ideals of traditional feminine behaviour. But then, as now, many ordinary women had to make a living, and more than we might expect have left their mark on the historical record.

References and Resources

- Claire Holleran, 'Women and Retail in Roman Italy' in Emily Hemelrijk and Greg Woolf (eds.), Women and the Roman City in the Latin West (Brill, 2016), pp. 313–330

- Sarah Bond, Pretty as a Pictor: Painters in the Roman Mediterranean (History From Below Blog)

Cambridge School Classics Project