From Quintus' little sister to the introduction of Barbillus as amīcus in Book I, there's lots to look forward to in the new edition. In this post, Director Caroline Bristow reflects on the narrative that students and teachers love and the changes you can expect from the new UK and International edition.

Submitted by Anonymous on Thu, 19/05/2022 - 14:10

The familia of Caecilius in full colour. The illustration appears on the opening page of Stage 1 in the new edition of the Cambridge Latin Course.

*Spoilers ahead*

The strength of the Cambridge Latin Course has always been its stories. Far more than just vehicles for language learning, they are key to the success of the Course. In the early days of the pilot teachers reported soaring motivation in Latin lessons. Students could not wait for the next instalment of the narrative, which appeared in little orange pamphlets. In fact, Pat Story, Director at the Project from 1987 to 1996, has often spoken of the soap-like appeal of the stories.

These days the stories are no less well-loved. Earlier posts in this series by Anna Karsten and Anna Barker testify to the way the CLC continues to speak to modern students, from the fanfiction the CLC inspires to the eternal popularity of Grumio. This has been particularly evident to me and the CSCP team at school visits in recent months. But conversations with teachers since 2017 have also helped us identify which stories seem strange or outdated to students in today’s classrooms. Pupils at Rugby High School and King’s School in Peterborough told us that their enthusiasm for the ancient world has led them to wonder what life was like for the people we do not often hear about. We agree. In this edition you will find improved representation of women, people of colour, those with disabilities and marginalised groups such as enslaved men and women, as well as new opportunities for critical engagement with the Roman world.

***

The new edition is still peopled with the characters and overarching storyline that students love. Book I, set in Pompeii in the first century AD, is based on the familia of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus. Beginning in Pompeii, students are introduced to Roman Italy and its wealth of archaeological evidence, such as the house and business records of Caecilius himself. There are many opportunities to develop skills of historical investigation as well as a sense of investment in the familia of Caecilius, whose members we follow in subsequent books.

In Books II and III, Caecilius’ son Quintus visits two very different provinces of the Roman empire, Britain and Egypt (specifically Alexandria). In Egypt he is joined by characters familiar from Book I: his sister Lucia; Clemens, a man previously enslaved in Caecilius’ household; and Caecilius’ friend Barbillus, a Syrian merchant living in Egypt. These books introduce our villain, the Roman politician Salvius, as well as a host other characters, including Togidubnus, the British king who falls victim to Salvius’ schemes, and his wife Catia.

Set in the provinces of Britain and Egypt in Book II and III, students encounter the vast geographical and cultural range of the empire. This presents opportunities to explore the experiences of different people within the Roman world, as well as the different methods of conquest and subjugation employed by the Romans. Britain is, at the time of the stories, a relatively new province where military conquest is ongoing. The political and social landscape is very different in Egypt, which had been subject to foreign rule for longer, first Persian, then Greek and Roman. The city of Alexandria also provides students with their first example of a large, prosperous cultural centre, so that when they come to study Rome they have a relevant point of comparison. That the first such city considered in depth is North African also challenges Eurocentric views and acknowledges the deeply complex and interwoven cultures of the ancient world.

Book IV brings the series to Rome for its conclusion and the comeuppance of Salvius. Lucia re-enters the narrative and the machinations of the imperial court take centre stage. As in previous editions, Rome is deliberately made the final location of the story. We finish at the seat of imperial power, having seen how that power affects the lives of people across the empire. By this point, students will have developed the skills of critical analysis necessary to engage with evidence from ancient Rome and to draw nuanced and complex conclusions. This setting also provides a natural ‘jumping off point’ to authentic classical Latin literature. In acknowledgement of this, Book IV contains more Latin sources in translation as part of the cultural background material and students are asked more challenging questions when it comes to analysis and literary criticism.

***

One character in particular might have caught the attention of UK and International teachers. When the North American 5th edition was released in 2015, Caecilius and Metella gained a daughter, (Caecilia) Lucia. We are delighted to welcome her to the new edition. Lucia allows us to explore the lives of Roman girls and issues specific to their experience, such as arranged marriage and political disenfranchisement, as well as offering a new viewpoint on events. Also making her way across the Atlantic is the artifex, Clara, replacing Celer in Book I. Clara helps us improve the visibility of the many working women in Pompeii. You can read more about both these characters in upcoming blogposts in this series.

When it comes to the representation of women, the story vēnālīcius must be one of the most discussed of the entire CLC. Modern students react with distaste to what they perceive as Caecilius’ ‘creepy’ behaviour as he inspects Melissa before purchasing her, while her ‘coquettish’ response feels outdated and out of place. Her objectification by the men of the household becomes a punchline to one of the Course’s most notorious jokes; Metella, it seems, is not happy with the arrival of the young, pretty slave-girl. Students today are much more aware of power dynamics and misogyny, not to mention issues of consent and sexual assault: for an excellent discussion, see Joffe (2019). In the new edition, this story has been replaced with ōrnātrīx in which Melissa and her point of view is centred instead of her enslavers’. In this story, and throughout the books, the tropes of the “loyal” or “hard working” slave are avoided, following the advice of specialists on appropriate language use. We hope the new edition helps enable teachers to interrogate Roman imperialism and enslavement. The books have been extensively reviewed by individuals of different identities and from a variety of backgrounds, and we have listened to their feedback and ideas; a huge thank you goes to all those people for their invaluable critical friendship and advice.

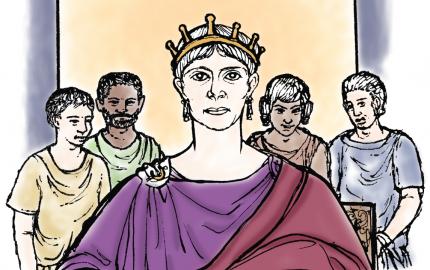

Another major development for the North American 5th edition was the colourful line drawings which accompany the stories. The popular misconception of the Roman world as predominantly white, inhabited by people with white skin, in white garments, surrounded by white buildings and statues, is not easily rectified by black and white line drawings. Attempts were made in 2015 to render more appropriately the skin colour of characters from provinces around the Mediterranean. In pictures of crowd scenes the team attempted to convey, through different skin colours, a sense of the multi-cultural nature of (in particular) Pompeii, Rome, and Egypt. This change was adopted for the new UK and International edition, but this work remains a form of estimation or ‘best guess’: there is insufficient evidence to calculate what proportion of people in any area of the Roman empire had a particular skin colour. We only know that human appearances varied then as much as they do now, and communities were not ethnically homogenous. One prominent character who has been re-drawn to better reflect his Greco-Syrian heritage and culture is Barbillus, who now appears as a close family friend in Book I in addition to his major role in Book II. You will meet Barbillus in the next post in this series.

References and Resources

- Joffe, B. (2019), 'Teaching the venalicius story in the age of #MeToo: a reconsideration', The Classical Outlook, Vol. 94.3, pp. 125-138.

- https://naacpculpeper.org/resources/writing-about-slavery-this-might-help

Cambridge School Classics Project